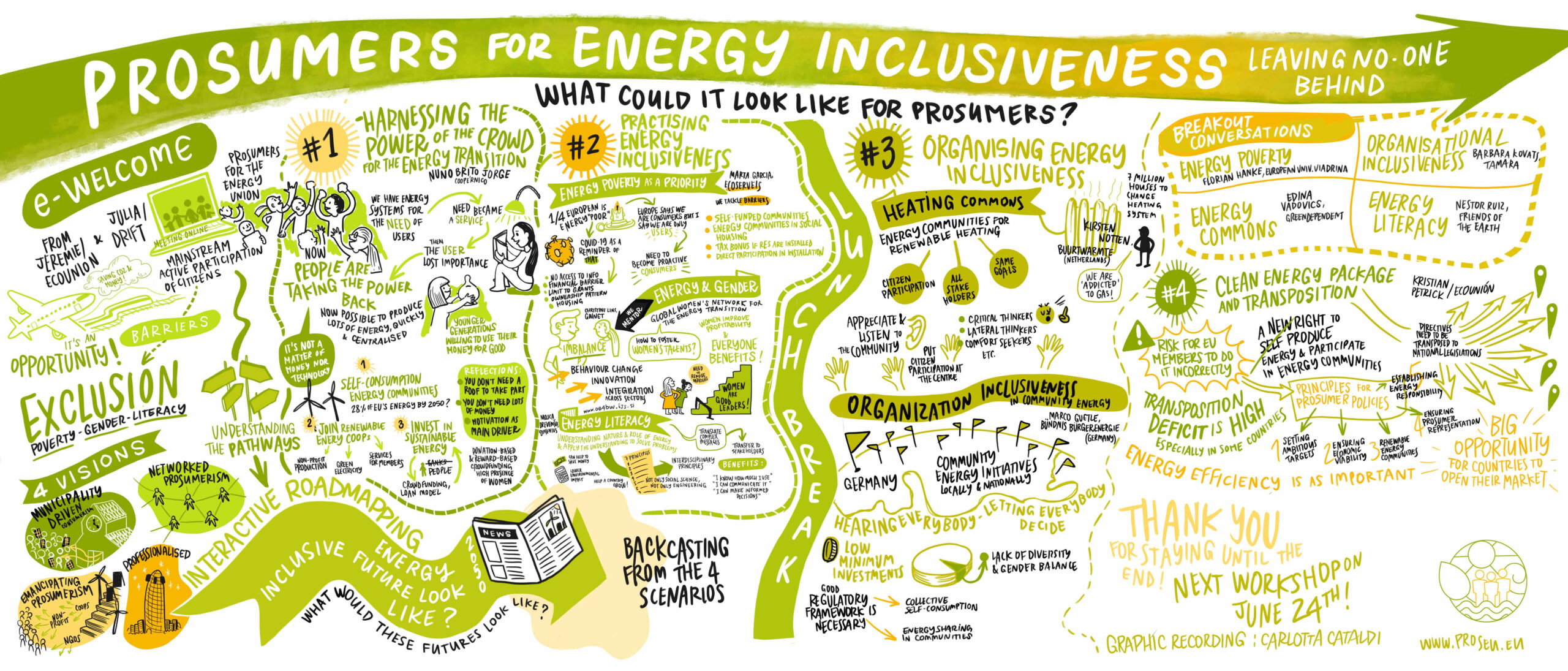

Prosumers for energy inclusiveness: leaving no-one behind

‘Prosumerism’ – where an energy user both produces and consumes energy from renewable sources – is an example of social innovation that is expected to play an increasingly important role in the energy transition. The SONNET sister project PROSEU explores how to enable the mainstreaming of prosumerism in Europe and what will be the role of prosumers in the future energy systems. What will a desirable energy future look like for prosumers? Will it be inclusive or only for the privileged? This discussion was the focus of a recent e-workshop organised by the PROSEU project‘s partners ClientEarth and eco-union.

The production of renewable energy is on the rise in Europe. A large role is reserved for ‘energy citizens’ who produce energy. These prosumers could generate up to 45 percent of the European Unions’ electricity needs by 2050, out of which 37 percent could be produced by collective projects and energy cooperatives. Individuals and collectives are no longer mere consumers of energy; today, many produce renewable energy and actively engage in energy markets.

Exploring the future of prosumerism means exploring the question: will the future of prosumerism be inclusive, or will it be for the privileged only? Which side of this spectrum becomes dominant will depend on key societal conditions, such as infrastructural, political, and technical factors, the degree of complexity of prosumer-related bureaucracy, as well as pricing (dis)incentives and subsidy schemes. In addition, socio-economic and cultural factors, such as participants’ socio-economic statuses, financial means, gender, social capital, as well as ‘energy literacy’, will determine to a considerable extent who participates in prosumer initiatives and how.

Direction 1: Towards an inclusive energy future

This scenario envisages collectives, whether public or private, that engage in the production and consumption of energy, while holding public interest as their main motivation. They ensure that a wider community benefits from their activities – one that extends beyond a narrow circle of initiators and shareholders. Diversity in the composition of (advisory) boards and executive committees are actively encouraged, just as diverse (community) members are empowered to participate and share skills and expertise. There is commitment to democratic decision-making and the voices of the lesser heard are amplified. Everyone is deemed worthy of benefitting from the solutions.

Direction 2: An energy future for the privileged

In this scenario, individuals or collectives are primarily interested in their own and/or mutual interest, which forms the starting point for redistributing benefits amongst themselves. They generally have the financial means, expertise, and social/professional networks to facilitate their venture into prosumerism. Alliances are built for mutual convenience, serving as an extension of self-interest: to have access to a secure, affordable, and renewable energy supply. The mainstreaming of privileged prosumerism could very well skew the market for a happy few that can afford it, while prices, perhaps even the access to prosumption itself, become prohibitive for all others.

The two directions may appear as extreme opposites. However, just as a privileged system may not be all bad (e.g. it may create safeguards to avoid energy poverty, albeit in a top-down manner), an apparently inclusive system can have a number of hidden pitfalls that weaken its intentions.

While inclusiveness is a guiding principle in many civic or public-led collective initiatives, these may unwittingly be perpetuating some of the exclusionary and privileging tendencies of today’s societies, especially in the largely unregulated niche of prosumerism. They may, for example, implicitly favour participants of a certain gender and of sufficient financial means, as well as participants that have the expertise and time to be more closely involved in decision-making. Cooperatives are, after all, private organisations that are free to focus exclusively on the narrow circle of their members.

The possible futures for prosumerism will, in reality, lie somewhere between the two extremes presented here. For example, municipalities are stepping up as guarantors of a more inclusive energy future. Prosumer collectives are joining forces to network and lobby together for their own inclusion in energy systems. Even though current societal conditions are favouring more exclusive forms of prosumerism and energy futures, initiatives are stepping up in a growing movement for more energy justice.

On behalf of the PROSEU project we invite you for the next e-workshop on 24 June which will discuss “Future energy systems: Prosumer islands or a new IoT community?“.

The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 837498.

The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 837498.